I am spurred into action this morning by my good friend Joe Henderson’s post about me on his blog over at www.alaskanarcticexpeditions.com, if you haven’t read his stories before you should, they are essential reading for all things alaskan malamute and real arctic travel.

I was lucky enough to be back travelling with Joe and the team after a gap in 2011 and what a vintage year 2012 was. The Arctic and the Arctic travelled in the company of 22 boisterous, feisty and enthusiastic alaskan malamutes is such a joy and one hell of a life tonic!

Meet the team 2012—Farmer, Shorty and Champ in lead (L to R), closely followed by Dino, Hippy and Texas and in the third row we can, just, see Mitch and “little” Savage followed by 14 more team mates.

At the heart of an expedition is their lust for travel, they are just as curious as Joe and I to see what lies round the next mountain, bluff or creek and that’s the thing about such an old and, I think I can say this, cultured breed as the alaskan malamute, they make ideal team mates to us humans.

This year I often travelled out in front of the team on ski or snowshoe, a fantastic place to be and the best place to appreciate what the dogs are doing. It’s also a demanding, heart pounding experience, the vim and pure vigour of the dogs is continuous, their panting and excitement is in your ears and on your tail, almost catching you and leaving me little space to grab a picture!

On some days, particularly later in spring, when the snow is right for modern cross country skis, I have the edge on the dogs and I can put a comfortable distance between them and me and it gives me a little space to reflect and roam in my imagination—it’s remarkable how we have been moving as one entity for weeks, humans and dogs walking and jogging, so closely attuned, matching each others pace and ardour. It can feel like we were made for each other, like we are one pack, and to a large extent that is the truth—malamutes, as one of the most ancient breed of dogs, have been our companions, and we there’s, for an extraordinarily long time in an interdependent relationship. A relationship that has allowed both humans and malamutes to flourish in what would otherwise be a very hostile environment.

Looking at the team now—Farmer, Shorty, Champ… and Joe too—I remember, and I say this with no exaggeration, that we are seeing just the tip of a very ancient story.

I thought it’s about time I posted some malamute photos – I guess I am missing these dogs with not having travelled to the Arctic last winter.

So here they are, a picture of obedience, all watching and waiting for their master’s voice, and that is definitely not mine, I just happen to be standing next to Joe Henderson with camera in hand. It’s a remarkable thing to see but Joe’s relationship to his dogs is so close that he just has to give the command and the team instantly springs into action, a simple “ok” and the power of twenty two malamutes’ eager fury is unleashed, a formidable force that moves thousands of pounds of expedition gear through deep untracked snow all day long. Anybody who owns a dog knows that training a pup can be a handful but training twenty two head strong malamutes to not only obey voice commands but to work together in unison, putting aside doggish distractions and team rivalries, is a remarkable feat and boy can they be distracted and unruly when they are not at work!

Camp time is filled with little light provocations

and playful revenge

that tests each of their limits and strengths, they really do like nothing more than to play, posture and settle scores within the pack hierarchy.

At times the posturing amongst “teenagers” can be fierce, this is Howdy trying out his snarling, snapping best, asserting his own sense of his position within the pack, but Tip and Dino really are not having any of it, their placid demeanor says it all, they can see through the posture and they are not bothered.

Other “teenagers” in camp, like Petra, can’t get enough of us humans

and will pull any kind of stunt

to give you a big wet lick.

Joe’s malamutes are brought up from birth with heaps of human contact and love and they are like family. As fierce as the dogs can be in their own social order they are the gentlest of human companions and this seems to be at the crux of Joe’s relationship to his team, their trust and respect for him is absolute and they will follow his every word.

FURTHER READING: To read more about these amazing dogs, visit Joe Henderson’s website and check out his magazine articles: www.alaskanarcticexpeditions.com/articles.html

In winter the boundaries of land and sea become blurred and can be a little unfathomable. Often there is no easy telling whether you are on solid ground or floating on ice, and were it not for the occasional tideline of flotsam you would not have any idea that you were on the beach at all.

In sheltered bays great swathes of twigs, trunks and stumps collect along the shoreline, perfect for firewood.

Impressive as some of these logs are, and a little ambitious as firewood, the really big question is where do they all come from? There is not a standing tree in sight, nor do any grow anywhere near Alaska’s north coast. Apparently they come from Canada, washed down from deep inland along Canada’s longest river, the 1080 mile long Mackenzie River, and then on out into the Arctic Ocean where they drift with the currents, become locked in sea ice each winter, and eventually get tossed up on an Alaskan beach – a long, long journey.

In the same way that you might pick up a shell on beach I have kept a small log from this beach, at first selected as firewood but at the last minute reprieved and saved as a memento.

A little theatrical maybe, but I’ve made a stand for my log and it lives on display in my home. I think it looks a touch hyperreal almost like a cartoon log, anyway it’s much admired for it’s twisting growth and shiny patina and never fails to charm with the possibilities of its life story. It’s speculative but my best guess, from asking around, is that it is black spruce from a tree that grew on the banks of the Mackenzie in an exposed and windy spot, which gave the wood its pronounced twist.

I hadn’t thought much as to the specifics of its age until the other day when I was in Rome and visiting the botanical gardens. Looking at the label for two tall stone pine trees, it declared, with a little pride, that these one and a half foot (forty five centimeter) girthed trees were over 200 years old. It got me thinking of my log.

On my return I sanded and polished the end of my log, I needed to count the growth rings. To my astonishment this two inch (five centimetre) wide log is in excess of one hundred and fifty years old. Now that is slow growing and I can only image just how old some of the big logs on that beach were!

Much of the Arctic north of the treeline, away from the classic destinations and the hyperbole of adventure, can be flat and featureless and more than a little desolate.

Still, it has its charms and on a grey day as the clouds thicken it creates its own kind of subtle and nuanced excitement, a perceptual challenge, a disorientating experience where the landscape loses definition and has little measurable depth beyond the immediate foreground.

Snowy white and light conspire to create a world that is not only challenging to see in but also to photograph. It is an interesting question, what can and can’t be photographed? My archive of Arctic photos has a heavy bias and to look at it you would think the sun was always blazing, the skies blue, the mountains steep and dramatic and of course we try to look heroic too as we pose or pass by the camera in parkas and snowshoes. In a sense everything appears picture perfect, but the actual reality of the Arctic, the one that keeps drawing me back year after year, is a very different one, it is more opaque and not so visible to the camera and to my eye it is no less stimulating for it.

Sometimes the only reference point in a world that can appear to have lost it’s third dimension is yourself, all around space appears to close in. Travelling forward you strain your eyes and try to determine where you might be heading, occasionally you might glimpse something shadowy, a large object in the distance, at last you have something to aim for, only to see it pass by you thirty seconds later, a small log embedded in the sea ice. Or more seriously there was the time we saw a grizzly bear up ahead, prematurely woken from his winter slumber—scary—and it initiated a full state of alarm on our part, only to see him mutate into a small seal nearby that then promptly vanished down a hole through the ice!

A grey day in the Arctic is never boring and is often mind bending.

.

It may be surprising to some that I am not a great believer in the significance of photographs, perhaps a heresy and doubly so as I am a professional photographer, a peddler of seductive images. Still when it comes to the Arctic I can’t help myself and I am seduced, as many of us are, by the Arctic’s extraordinariness and the possibility that I might just be able to bottle some of it and take it home. After a trip a few images amongst a stream of many become my mementos, just as this image from 2009 has done.

On this day Joe Henderson and I, and his all important malamutes, are mid way across a 120 mile traverse of rolling tundra. Over several days we have travelled from the Brooks Range mountains that you can see in the distance, bathed in evening sunlight, and are heading for the Arctic Ocean to the north. We are camped next to a lake, which is invisible beneath the snow, the tents are set and the dogs are picketed, it’s a tranquil evening. I am standing on a low bluff photographing as the mountains briefly reveal themselves, a photographic moment. The day has mostly been overcast with a heavy lid of cloud and we have travelled through an all white terrain with little in the way of graspable features, not an easy day for photography with a flat light that fails to render more than two dimensions and is tricky to navigate in three. It’s little wonder, with such a sensory void all around, that I find myself daydreaming, and I am sure that I am not the first person to analogize seafaring with arctic travel, but on this day it did feel like we were at sea in a rolling oceanic swell with only dead reckoning to guide our course. Hove to that night and with this brief appearance of the mountains I regained my bearings and confidence in photography’s ability to distill a little bit of the Arctic.

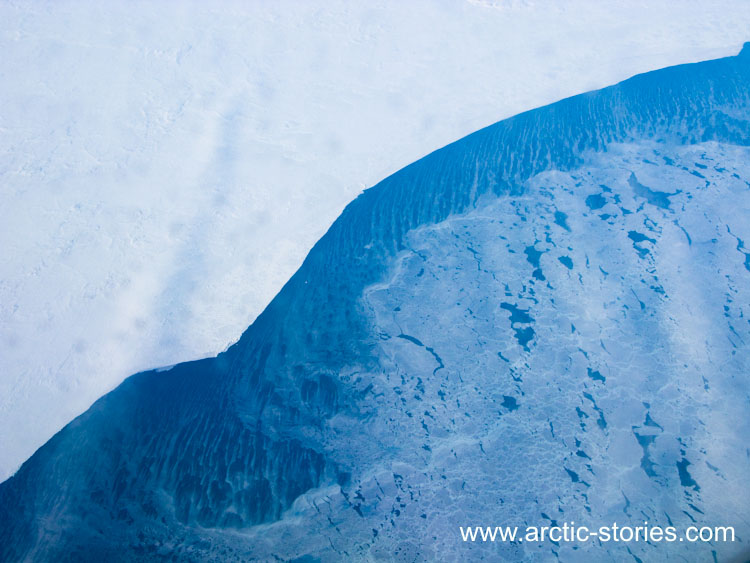

Flying from England to Alaska is a visual treat, not because of the latest movie showing on your seat back tv, no, because of the views out of the window. Flights usually fly over the Greenland icecap, across Davis Straight and clip the bottom of Baffin Island before continueing across Canada.

As we drift over the terrain I am fascinated by its enormity, often peering down with binoculars trying to gain a purchase, find something human scale amongst the disorientating abstracts, even a single tree would give me my bearings. I marvel at how few people may have visited the valley, the mountain, the glacier below – in the absence of clues it’s easy for imagination to roam, to speculate that it was perhaps a long time ago, perhaps a hunting party from a culture that has left little trace today.

The landscapes become softer as we meet the tree line and from a European perspective slightly more intelligeable as a place of shelter and sustenance. Whilst there is certainly a larger human presence it’s still a place for extremophiles, not least the ingenuous native cultures and in more recent history the tough frontiersmen, mostly fur trappers and prospectors who went on to translate their experiences into cash and some classics of literature – the kind of book I think I’m going to read on a long flight North, Samuel Hearne, Robert Service, Jack London, et al, but really the view out the window is more telling and compelling.

As the hours go by what started out as the odd incongruous straight line bisecting the forest steadfastly increases to a zany maze of hieroglyphs. I have no idea what this one represents, strangely there were no buildings in all those cleared patches of forest.

Louise and the Chena River

And this is the forest for real a few miles out of Fairbanks, Alaska, ideal for stretching your legs after a long flight!

<< Older posts

|

no comments